Wait, Rap Music Used to Be About Love?!

December 18, 2025

White Woman Godzilla

January 1, 2026

Wait, Rap Music Used to Be About Love?!

December 18, 2025

White Woman Godzilla

January 1, 2026Love and Music Series,

Part II

I love so much about 80s music. As a little girl, I’d watch the videos for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” on loop. I knew for certain that when I grew up, I would wear massive curls that would frame my brown oval-shaped face. For the gear, I’d rock second-skin zip up acid-wash denim, or tiny leather skirts with and pointed-toe pumps. I’d sashay through suburban Los Angeles like a Black bombshell.

So, I was surprised when recently I was caught completely off guard by Rick Astley’s 1987 chart topper, “Never Gonna Give You Up.” It’s signature 80s with all the fixins’: big hair, oversized blazers, denim-on-denim, a Black man used as a prop, and more than anything else, gleaming white teeth. It wasn’t the aesthetics that threw me—these same elements are fashionable today. It was the lyrics. It occurred to me that it had been a long time since I’d heard a man emphatically proclaim his “love” qua devotion, to a woman.

It’s strange that Astley’s hit would be strange for a number of reasons. For nearly 1000 years, paeans to so-called “romantic love” had been among the central messages of all songs made in the West. And of course, the majority of them had been made by men.

But, there’s even more to it than this. Many Americans may not know that “romance” is not an innate, biologically-determined way for men and women to relate to one another. As it turns out, it is simply a medieval Western cultural pretension.

Romance as we know it was born in 12th century France. (There was an earlier form of romance that I’ll get to in a future post.) Roving singer-poets, known as troubadours, toured the slice of Western Europe that today includes much modern-day France, Spain, Italy and Portugal. They regaled audiences with tales filled with deep emotions, passionate sexual attraction among the nobility, and loss. It is these three elements that comprise a “romance” or a “romantic love.”

The troubadours were a huge draw. Their serenades were so popular that they changed the way people talked about their lives and sexual affairs. Their songs helped provide the grammar for what we now call the “romance languages.”

This style of romance was a smash success from its inception. But it was never meant to be for everyone. The romantic tales told by the troubadours were of a “courtly love,” one in which a gallant knight battled brutes to rescue his amour. That is, these nearly 1000-year-old Western European tales is where we get the idea of knights in shining armor rescuing ladies. And in case you didn’t catch it, this was only ever meant to be about the nobility—commoners need not apply.

Lancelot and Guinevere are considered the first model of courtly love. He, a knight, she a queen, married to the most powerful king in all of the known world, King Arthur. All of them were fictional characters. But, here’s another important thing: that she was married and above his station made her entirely inaccessible. (This is the origin of the idea of a woman being “out of his league.”)

It was her inaccessibility that made pursuing a sexual affair with her exciting, and even dangerous. Because a knight could not just run up on a woman of that pedigree. She was a married royal. He, a mere noble at her service. So, knights and other men (of what we might today consider the middle, or upper-middle classes) used the idea of romance to envision themselves as courageous and honorable. Noble women used romance to suggest they were worthy of this brand of love-as-pedestalling. Their connection was both exhilarating, and doomed by this tale of love that, curiously enough, was also scandalous.

And yet, tales are all they ever were. There is little evidence to suggest that this was ever the way knights or any other men actually treated women on any large scale. Indeed, while most of the troubadours were men, there were a handful of women going around singing about the pretenses of these narratives, and the phony men who composed them.

That was not the worst of it. Perhaps more troubling for those of us who live under the guise of a multiracial democracy, the courtly love that would later be our romantic blueprint was reserved for elite women, and the men who wished to be put on by them. The knights were prototypically found fighting first for king and country, and secondly for the hand of a “fair maiden.” Make no mistake—these knights were not about to lower themselves for a peasant woman, or for a woman with dark or so-called swarthy skin. This was before the birth of race, but after the rise of color prejudice in Western Europe. Yes, in most of the many surviving depictions of Guinevere herself, her shining white skin (and often blonde hair) are waxed ad infinitum.

By the 19th century, romance evolved from being about a courtly love that was literally an extramarital affair, to being the reigning ideal for finding a life-long partner. This meant all the original valiant acts—standing up for women, defending their honor, never pressuring them for intimacy, humbling yourself in their presence, putting their needs first, giving them gifts like flowers—plus it tacked on the requirement of men in long-term partnerships during that period: providing for their women and children financially. Suddenly whole new populations of women who had only ever read about romances were expecting to have one. Men, of course, were expected to deliver the romantic treatment. Still, it was not to include any of the aforementioned “low” sorts. Could, for instance, the Irish women who arrived in America during the wake of famine expect to be courted by Anglo-Saxon men? Hardly. It goes without saying that Black women who were enslaved were typically raped and subjected to other forms of assault—no romances for the readily violable.

Still, Americans remained fervently attached to the idea of romance. Riiiggghht up until the feminist movement. The first wave opened men’s eyes to the “problem” of romance. To the vexed expectations among a growing number of women to “have it all”: to be equal to men, and to be “courted.”

Many men were content to play the game so long as women understood their place, and were the right types of women: those who were attractive and of high status. With the first wave of feminism, men started to ask why they’d work so hard to please women who weren’t willing to be chaste, attractive, homemakers? How did women politicking in the streets need (much less deserve) the romantic treatment?

The first way out of romance arrived after the First Wave of Feminism. It was pornography. In rags like Playboy, men waxed lyrical about their hatred of romance.

The second, which came on the heels of the Civil Rights and Second Wave feminist movements—and what I consider in many respects to be porn’s public face—was misogynistic, and often misogynoir rap. For while men began consuming porn hard and fast in the 1950s—it was rarely discussed in polite company. But rap took America (and later the world) by storm beginning in the late 80s. It carried many messages, but one of it’s most enduring is the disdain of the “low” sorts of women. The hoodrats, the ratchet sorts. The poor white “Kim” types. But more than any other group, Black women.

* * *

How to contrast Rick Astley’s profession of timeless, romantic, devotion to an (undoubtedly white) woman in 1987, where he croons,

We're no strangers to love

You know the rules and so do I…

Never gonna let you down

Never gonna run around and desert you…

Never gonna tell a lie and hurt you

With N.W.A’s 1988 jump off “A Bitch Iz a Bitch”?

Yo, you can tell a girl that's out for the money…

But a nigga like me'll say "fuck you"…

Cause the niggas I hang with ain't rich

We'll all say "Fuck you bitch!"

Now what can I do with a ho like you

Bend your ass over and then I'm through

The romantic Astley thinks it’s his duty to do whatever he can for the (attractive, high status) woman who has him in his deep feels. Meanwhile, N.W.A. sees women who they describe as “snobby”— seemingly meaning that they have a high status or just standards these men don’t meet—as petty gold diggers. As “bitches” to be fucked and thrown away.

And it’s not just N.W.A. No one is a bigger figure against loving women (especially us “low” types) than Snoop. His mantra, we don’t love them hoes is nothing short of a brand and a global export.

The late 80s was the turning point in music. It was the beginning of commercial rap, that anti-romantic genre, finding its way to the top of the music game. Despite seeing a slide in its infamy since the Covid years, it is the most consumed form of music in America. And a good number of the most popular songs are about the hatred of women. (To quote Pulitzer winner Kendrick Lamar, “Love one of you bucket-headed hoes? No way!)

You may have never noticed it before, but popular rap has long been anti-romantic. This is the real difference between commercial rap, and nearly every other genre of music. It tells men do not get caught up tryna romance a woman, especially one who thinks she’s “a lady” deserving of the treatment.

Love and romance are not the same. Sexual love is a deep care mixed with physical attraction. Anyone could feel this for any other person. But, our ideas of sexual love have been colonized by romance.

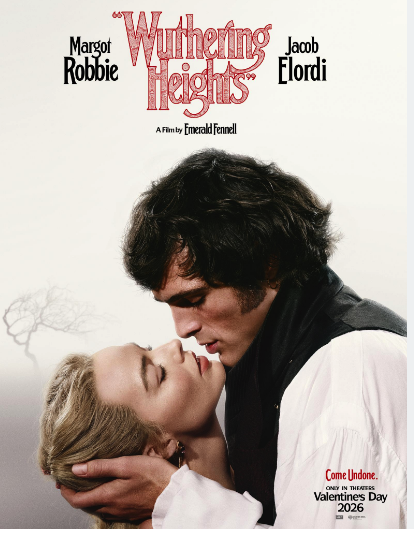

Romance articulates the rules used by men to court women. The men must be of at least middling status and perform the aforementioned valiant and financial acts. The women should be of a higher status, and as close to the apex of white hot as possible. It’s hetero-regulating. And since the 19th century, it has been used to legitimize, elevate, and solidify a sexual and emotional bond that is expected to end in marriage, largely of the well-to-do. Notice that most romantic stories star two rich white people. A good number take place in the middle-ages, up to the Victorian era (pre-women’s suffrage).

What happened to romance? The answer is simple. Romance began with a song. It was choked by the competing demands of the movement eras. Its die-off was triggered by 20th century mainstream porn and popular gangsta-bling rap.

But don’t worry. If you are not an elite white woman, who finds a slightly less wealthy, but still high-status brave man, you weren’t likely to have a romance anyway.

Learn more about romance’s white fetish, and how it marginalizes Black and other insufficiently white women in my latest book, The End of Love: Racism, Sexism, and the Death of Romance.